With such an interest in presenting the history and heritage of just about everything, the only surprise about the creation of a museum dedicated to the Silverstone Circuit is that it took so long to come about. Opened in early 2020, it is to be found on the outside of the circuit a little to the left of the main entrance. What you see looks like a new building, but in fact it is not, as Silverstone have taken one of the old steel-framed hangars from the war time use of the site, addressed some of the inherent issues in the structure and then adapted it to create a two storey “experience” which is intended both to inform enthusiasts and the public, house the BRDC’s vast historical archive and to be a facility to offer to schools and colleges to help promote careers in science and technology. Rather than simply presenting a series of static objects and displays, there are plenty of opportunities for visitors to “engage” and do things as well as lots of use made of the latest audio visual technologies. The building occupies 4000 square metres and there is a lot here, so the museum says you should allow a minimum of a good couple of hours to visit, and not the rushed 20 minutes or so that viewers of BBC tv’s “The Apprentice” saw a few weeks before my visit. I originally planned to go along in late 2020, with a group of friends as part of our Christmas get-together which we hoped, when we booked the tickets, would be possible in what we believed would be a post-lockdown world. Sadly, it turned out that in December 2020 we were only between lockdowns and the visit had to be deferred. Finally, with a semblance of normality resumed in 2022, I was able to find a free day to go and visit and use the ticket that had already passed the initial 12 month extension to its validity.

Silverstone is probably most famous as the long term home of the Formula 1 British Grand Prix, and accordingly there are a couple of (replicas of) modern Formula 1 cars in the expansive entrance foyer, with this 2021 Aston Martin AMR21 on the ground and another car, a Mercedes, suspended from the ceiling.

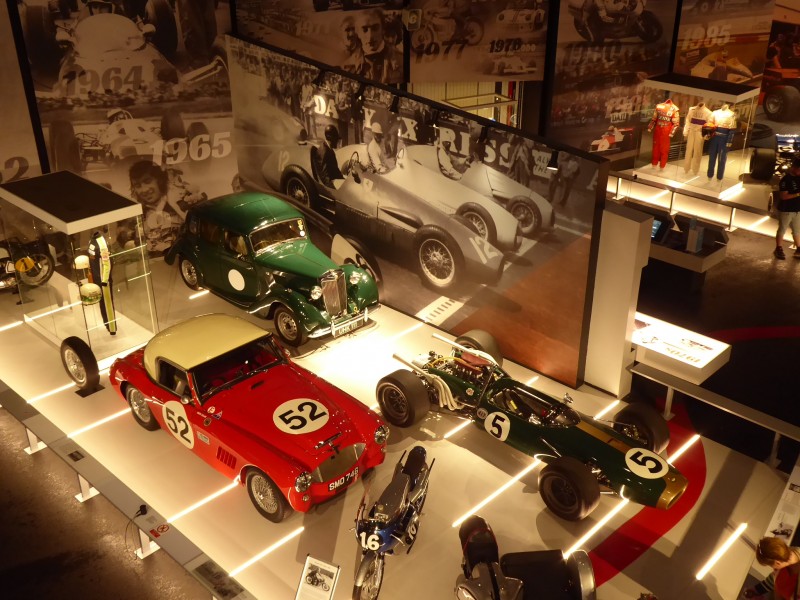

After going through what the facility calls a “pre-race briefing”, the tour starts on the upper storey and almost immediately you can look down form what amounts to a viewing gallery to see some of the layout of the ground floor, though it could be a while before you get there, depending on how long you spend studying all the detail that is presented o this second storey. As you look down, you see a true panorama of cars and bikes, heroes, massive images, maps, all manner of video-based interactive exhibits, the heads of various living, breathing and very helpful volunteers and, above all, space. It stretches to the building’s very extremities.

If you are expecting a museum that is basically full of racing cars and bikes, then you are perhaps going to be disappointed, as that is not really what the Silverstone Experience is all about. There are some, of course, from all genres of motor sport. See here were examples of Touring Cars as exemplified by the Volvo 850 driven by the likes of Rikard Rydell in the mid 90s, to older cars now used in historic racing, such as the Austin Healey 3000, which would also have been seen in action here when new. As was the 1952 MG YB. This car won the under 1500 cc class at the first Daily Express International Trophy touring car race at Silverstone in 1952 driven by Dick Jacobs. It won the same class in 1953 and 1954.

Instead, what you get, spread out over two floors of the building, is a combination of a history lesson on the Silverstone site and of all the aspects that go up to make motor-sport possible. There’s a vast amount of information presented on wall panels and in the details of the displays, with huge numbers of artefacts, so if you only spend a couple of hours here, you may well just be scratching the surface of what is here.

The tour starts upstairs and the first part of what you learn is the history of the Silverstone site. Have you ever wondered why the various curves and straights of the circuit are so named? There’s a historical or geographical association for every single one of them. Many will know that the site was used in the second world war by the RAF where it was used to train pilots and repair planes, including the Wellington bomber. But it goes back hundreds of years, where as far back as the 11th century there was monastery here – hence Luffield, Priory, Chapel and Abbey – and then by the 1800s it was used as farmland, part of the extensive Stowe estate. During the second world war,, along with nearby Turweston Airfield, the site was developed to house an RAF base for the training of Wellington bomber pilots. When WW2 came to a close such a facility was no longer needed and the future of the site was uncertain. But racing enthusiasts were looking for new circuits, as pre-war venues had been taken over by the military. Silverstone’s wide, open space and runways would prove to be the perfect location for what would become one of the most famous race tracks in the world. Silverstone was first used for motorsport by an ‘ad hoc’ group of friends who set up an impromptu race in September 1947. One of their members, Maurice Geoghegan, lived in nearby Silverstone village and was aware that the airfield was deserted. He and eleven other drivers raced over a 2-mile (3.2 km) circuit, during the course of which Geoghegan himself ran over a sheep that had wandered onto the airfield. The sheep was killed and the car written off, and in the aftermath of this event the informal race became known as the Mutton Grand Prix. With the termination of hostilities in Europe in 1945, the first “official” motorsport event in the British Isles had been held at Gransden Lodge in 1946 and the next on the Isle of Man, but there was nowhere permanent on the mainland which was suitable. In 1948, Royal Automobile Club (RAC), under the chairmanship of Wilfred Andrews, set its mind upon running a Grand Prix and started to cast around public roads on the mainland. There was no possibility of closing the public highway as could happen on the Isle of Man, or the Channel Islands; it was a time of austerity and there was no question of building a new circuit from scratch, so some viable alternative had to be found. A considerable number of ex-RAF airfields existed, and it was to these the RAC turned their attention to with particular interest being paid to two near the centre of England – Snitterfield near Stratford-upon-Avon and one behind the village of Silverstone. The latter was still under the control of the Air Ministry, but a lease was arranged in August 1948 and plans put into place to run the first British Grand Prix since the RAC last ran one at Brooklands in 1927 (those held at Donington Park in the late 1930s had the title of ‘Donington Grand Prix’). In August 1948, Andrews employed James Brown on a three-month contract to create the Grand Prix circuit in less than two months. Nearly 40 years later, Brown died while still employed by the circuit. Their first two races were held on the runways themselves, with long straights separated by tight hairpin corners, the track demarcated by hay bales. However, for the 1949 International Trophy meeting, it was decided to switch to the perimeter track. This arrangement was used for the 1950 and 1951 Grands Prix. In 1952 the start line was moved from the Farm Straight to the straight linking Woodcote and Copse corners, and this layout remained largely unaltered for the following 38 years.

Despite possible concerns about the weather, the 1948 British Grand Prix began at Silverstone on Thursday 30 September 1948. The race took place on 2 October. The new circuit was marked out with oil drums and straw bales and consisted of the perimeter road and the runaways running into the centre of the airfield from two directions. Spectators were contained behind rope barriers and the officials were housed in tents. An estimated 100,000 spectators watched the race. There were no factory entries but Scuderia Ambrosiana sent two Maserati 4CLT/48s for Luigi Villoresi and Alberto Ascari who finished in that order (notwithstanding having started from the back of the grid of 25 cars) ahead of Bob Gerard in his ERA R14B/C. The race was 239 miles (385 km) long and was run at an average speed of 72.28 mph (116.32 km/h). Fourth place went to Louis Rosier’s Talbot-Lago T26, followed home by ‘Bira’ in another Maserati 4CLT/48. The second Grand Prix at Silverstone was scheduled for May 1949 and was officially designated the British Grand Prix. It was to use the full perimeter track with a chicane inserted at Club Corner. The length of the second circuit was exactly three miles and the race run over 100 laps, making it the longest post-war Grand Prix held in England. There were again 25 starters and victory went to a ‘San Remo’ Maserati 4CLT/48, this time in the hands of Toulo de Graffenried, from Bob Gerard in his familiar ERA and Louis Rosier in a 4½-litre Talbot-Lago. The race average speed had risen to 77.31 mph (124.42 km/h). The attendance was estimated at anything up to 120,000. Seen here is a replica of that famous ERA R14B/C. Whilst all the other display cars are off limits, because this is a replica, visitors are actively encouraged to sit in it. I’ve seen the real version of this car in action at venues like Prescott and Shelsley Walsh but understandably, never been able to try it out for size before. And now I could. I can tell you that if getting in is not easy, getting out is harder! And it is not exactly comfortable when you are in, either.

Immediately after the war, money was very tight and cars were in short supply, so a new and lower cost formula soon became popular for cars with sub 500cc engines. This is one such example, a 1948 Cooper Mark 2 500cc. Also known as the T5 (Type 5), this was a 500cc (predecessor to Formula 3) open-wheel racing car designed and built by the Cooper Car Company at Surbiton, Surrey, England, in 1948, and was the first production car made by Cooper. It was a successor to 1946 Cooper 500, which was a prototype. 12 cars were built. It was powered by a 45 hp 500 cc JA Prestwich Industries (JAP) 4B Speedway single-cylinder engine, but had the option of being converted to a lengthened wheelbase version, to be able to use a 70 hp 1,000 cc JA Prestwich Industries (JAP) or Vincent-HRD V-twin. It also notably won the first ever Grand Prix at Silverstone in 1948, competing in the 500 cc class, being driven by Spike Rhiando.

Showing just how quickly race cars evolved, this is a Brabham Repco BT19 Formula 1 Car from 1966. The BT19 competed in the 1966 and 1967 Formula One World Championships and was used by Australian driver Jack Brabham to win his third World Championship in 1966. The BT19, which Brabham referred to as his “Old Nail”, was the first car bearing its driver’s name to win a World Championship race. The car was initially conceived in 1965 for a 1.5-litre (92-cubic inch) Coventry Climax engine, but never raced in this form. For the 1966 Formula One season the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) doubled the limit on engine capacity to 3 litres. Australian company Repco developed a new V8 engine for Brabham’s use in 1966, but a disagreement between Brabham and Tauranac over the latter’s role in the racing team left no time to develop a new car to handle it. Instead, the existing BT19 chassis was modified for the job. Only one BT19 was built

It was raced after 1967 and the car went to Australia where it was on display for many years.

Dating from the early 70s is this Tyrrell Ford, as raced by Sir Jackie Stewart.

Wind the clock on two and a half decades and we get to this, the 1992 Williams-Renault FW14B, a Formula One car designed by Adrian Newey, used by the Williams team during the 1991 and 1992 Formula One seasons. The car was born out of necessity, as the 1989 and 1990 seasons had proven competitive for Williams, but they had underachieved in their own and Renault’s eyes. Newey started work on the new car soon after joining the team from March in mid-1990. He had designed a series of aerodynamically efficient and very effective cars for March on a limited budget, so with Williams’s greater resources and money he was able to fully develop his ideas. The all-new design (with the exception of the engine) showed enough promise to tempt Nigel Mansell to shelve his plans to retire from the sport and rejoin Williams from Ferrari. Powered by a 3.5-litre V10 Renault engine with its design and development led by Bernard Dudot, the car is considered one of the most technologically sophisticated to have competed in Formula One. By 1992 the FW14B featured semi-automatic transmission, active suspension, traction control and, for a brief period, anti-lock brakes. With the aerodynamics as designed by Newey and the active suspension invented by designer/aerodynamicist Frank Dernie, the car was far ahead of its competitors, such as the McLaren MP4/7A, Ferrari F92A or Lotus 107, and it made for a strong package. The FW14B was so successful that its successor (the FW15), which was available mid-season in 1992, was never used. The FW14 made its debut at the 1991 United States Grand Prix. The car was the most technically advanced car in competition, but various difficulties during the season stymied the team’s early progress. Nigel Mansell and Riccardo Patrese recorded 7 victories between them but the Drivers’ Championship was wrapped up by Ayrton Senna in the McLaren MP4/6, which had better reliability. Williams had the faster car throughout the balance of the season and it provided a run of good form in the midseason for both Mansell and Patrese. Mansell, in particular, had several retirements due to the then new-for-Williams semi-automatic transmission, with most of these retirements occurring while in a position to win races. Patrese was impressive on several occasions and retired while leading twice. McLaren’s superior reliability told in the Constructors’ Championship as well, as they narrowly took the title from Williams. A total of 5 chassis were built. Although there is little difference in appearance between the FW14 and FW14B, the FW14B has front suspension bulges on the body due to the addition of the active suspension system. In 1992, after further development work was done to the gearbox and aerodynamics, and electronics technology such as a traction control and active suspension system were added, the B-spec. FW14, known as the FW14B was introduced for the 1992 season. The FW14B was the dominant car that year and Mansell wrapped up the 1992 Drivers’ Championship with a then-record 9 wins in a season, whilst Patrese scored a further win at the Japanese Grand Prix. Patrese did not warm to the car as much as the FW14, as he preferred the passive suspension in that chassis, whereas the increased level of downforce generated by the FW14B suited Mansell’s aggressive driving style much better. The main visible difference between the FW14 and FW14B were a pair of bulbous protrusions above the latter’s front pushrods, which contained the active suspension technology. The FW14B also featured a longer nose section.The car had been present at the Australian Grand Prix the previous year, but Mansell had elected to use the regular FW14 in that race. The result was that there were many races in the 1992 season where Mansell and Patrese would gain 2 seconds per lap on the rest of the field, especially in the early laps, which made the FW14B far superior to even the next best car, the McLaren MP4/7A. Another example of Williams’s dominance that year was at qualifying at the British Grand Prix at Silverstone, where Mansell’s pole position-winning lap was a whole 2 seconds faster than Patrese, who in turn was a second faster than 3rd placed Ayrton Senna. Williams were clear winners of the 1992 Constructors’ Championship, but the season ended in acrimony as Mansell left the team after Alain Prost was signed, while Patrese moved to Benetton for his swansong season in 1993. Both versions of the FW14 won a combined 17 Grands Prix, 21 pole positions, and 289 points before being replaced with the FW15C for 1993. Given that current F1 regulations ban many of the technologies used by the FW14B and FW15C, these are considered among the most technologically advanced racing cars to have ever raced in Formula One. On 2 June 2017, the Williams F1 team celebrated 40 years in Formula One with a media day at Silverstone race circuit. The FW14B was driven for the first time since 1992 for a number of laps by Karun Chandhok. The car did several laps on its own around the circuit; it then performed 3 laps accompanying the 2014 Williams FW36 driven by Paul di Resta. A total of 6 chassis were built. The numbering continued from the FW14, so FW14B serial numbers 6 through 11 were built. In 2020, it was revealed that Sebastian Vettel bought Nigel Mansell’s no. 5 FW14B, the same chassis that won the 1992 F1 world title.

David Coulthard was the driver of this McLaren Mercedes MP4/15, with the car being used in the 2000 season

Recently arrived on loan from Mercedes‐Benz Grand Prix Limited is Jenson Button’s 2009 World Championship winning Brawn GP 001. The story of the Brawn Grand Prix team has become a modern Grand Prix racing legend. In December 2008, Honda F1 announced its intention to leave the sport with immediate effect after a disappointing season. This created an uncertain future for the team’s 700 staff members and two racing drivers, Jenson Button and Rubens Barichello. Knowing that their 2009 car was likely to be competitive, team principal Ross Brawn led a management buyout of the team and renamed them Brawn GP for the 2009 season. The car ran for the first time here at Silverstone, on the infield Stowe Circuit, three days before the last official Formula One test of the season in Barcelona. The car was an instant success, winning six of the first seven races of the season. Results tailed off in the second half of the season, as the team did not have the budget to develop the car, but even so, they won the Constructors’ World Championship with Jenson Button winning the Drivers’ Championship. In 2010 the team was purchased by Daimler and became the Mercedes Formula One Team.

Rather more recent is this Force India VJM06 which dates from 2013. This was designed and built by the Force India team for use in the 2013 season where it was driven by Paul di Resta and Adrian Sutil, who returned to the team after spending the 2012 season out of the sport. The car was launched on 1 February 2013 at the team’s base near the Silverstone Circuit, and is complete redesign of the previous year’s car. It was the last British-based F1 foreign car to utilize ExxonMobil fuels and lubricants before its use for Red Bull RB13 in 2017.

This one is Daniel Ricciardo’s Red Bull Renault RB10 F1 car from 2014, a Formula One racing car designed by Adrian Newey for Infiniti Red Bull Racing to compete in the 2014 Formula One season. It was driven by reigning World Drivers’ Champion Sebastian Vettel and Daniel Ricciardo, who was promoted from sister team Scuderia Toro Rosso after Mark Webber announced his retirement from the sport at the end of the 2013 season. The RB10 was designed to use Renault Sport’s new 1.6-litre V6 turbocharged engine, the Renault Energy F1-2014. The car was launched on 28 January 2014 at the Circuito de Jerez. Keeping with the tradition of naming his race cars, Sebastian Vettel named the RB10 as “Suzie”. The early stages of the RB10’s development were seriously limited by several recurring issues, with the team managing less than 100 kilometres (62 miles) of running during the first test in Jerez de la Frontera, less than any other team which attended the test.[10] The team—like fellow Renault-powered outfits Scuderia Toro Rosso and Caterham—were affected first by problems with the physical Renault Energy F1-2014 unit that prevented the individual components of the power unit from working together. Once these issues were resolved, the team experienced problems with the software governing the turbo unit. Red Bull also suffered from unique problems arising from the tight packaging of the RB10 chassis, which caused temperatures within the car to climb so high that parts started to burn. The team’s problems continued during the second test at the Bahrain International Circuit, where they were forced to run with the Energy Recovery System (ERS) disabled on Renault’s advice, robbing the RB10 of up to 150 bhp. Although Sebastian Vettel was able to complete over seventy laps of the circuit on the first of four days of testing, the team completed less than forty more over the remaining three days as the chassis was further plagued by mechanical issues. As the test ended, Red Bull had completed fewer laps than any other team save for Lotus and Marussia, and the fastest times recorded by Vettel and Daniel Ricciardo were outside 107% of the fastest time recorded during the test; had the test been treated as a qualifying session, neither Vettel nor Ricciardo would have qualified for a race. The final test of the season—also held in Bahrain—was little better; although Ricciardo recorded the car’s fastest lap time, it was still two and a half seconds slower than the fastest lap time recorded by Felipe Massa. When Vettel returned to the car, he failed to complete a lap before the car broke down, and team principal Christian Horner admitted the team had no idea when the problems with the car would be fixed. The start of the season was unfortunate for Red Bull, with technical problems causing Vettel to retire in the opening laps of the Australian Grand Prix. A second-place finish for Ricciardo was stripped due to illegal fuel flow throughout the race. Despite warnings from officials throughout the race, Red Bull used their own fuel flow system rather than the mandated FIA item, claiming the FIA unit was faulty. Vettel was able to achieve third place in Malaysia, though a botched pit stop and front wing damage forced Ricciardo to retire from the race. Ricciardo and Vettel would both go on to finish in the points at the Bahrain Grand Prix, finishing fourth and sixth, respectively. They would repeat this feat once more at the Chinese Grand Prix, with Ricciardo finishing fourth again, and Vettel behind him in fifth. The form of the RB10 improved at the Spanish Grand Prix, where Ricciardo achieved a third-place finish, and Vettel finished fourth, also ending Mercedes’s streak of setting the fastest laps of every race. Ricciardo repeated a third place podium finish in Monaco, managing to hound Lewis Hamilton in a battle for second after the latter had problems with his vision. Conversely, Vettel retired early on due to power unit issues. The RB10 took its first win of the 2014 season when Ricciardo won the seventh race of the season, in Canada. The win was also Ricciardo’s first in Formula One, while Vettel was also able to record his second podium finish of the season, finishing in third place. Red Bull were not able to repeat a great result at its home race in Austria, with Ricciardo finishing in eighth, and Vettel retiring for the third time, due to a lack of power, and later front wing damage. Ricciardo and Vettel bounced back to place third and fifth, respectively in Britain. Ricciardo gave the RB10 its second and third wins at the Hungarian and the Belgian Grands Prix respectively. The team finished second in the Constructors’ Championship, with Ricciardo finishing third in the Drivers’ Championship, beating Vettel, who finished fifth. At the final race of the season in Abu Dhabi, the Red Bulls were excluded from qualifying for having a front wing which was over the wing flex limits. As a result, the Red Bull cars were sent to the back of the grid. The team was, however, able to claw back a decent result with Daniel Ricciardo finishing fourth and the departing Sebastian Vettel finishing in eighth place.

And this Racing Point Mercedes F1 car is just a couple of years old, coming from the 2020 season.

Just about every Formula and category of motor racing has held races at Silverstone, some more familiar than others. This Formula 3 Reynard VW 873, designed by Adrian Reynard and raced by the Eddie Jordan Racing team, used by Johnny Herbert in 1987.

There’s a special display which focuses on the BRM team. Most of the historic BRM cars are to be found in the company’s private collection up at Bourne in Lincolnshire but there is one here to bring the wall panels to life, a P48/4 from 1960. The BRM P48 was a Formula One racing car raced in 1960. It was BRM’s first rear-engined car. With rear-engined cars in the ascendancy, BRM hastily reworked the front-engined, now five-year-old P25. The car proved to be slow and unreliable, and was replaced by the P48/57 the following year. Aside from the placement of the driver and engine, the P48 was mechanically the same as the outgoing P25. It featured the same 2.5 litre straight-4 engine producing 275 horsepower. The P48 also featured a single brake disc at the rear mounted directly to the gearbox. The rear bodywork was cut off to aid cooling, which exposed the unlovingly nicknamed “bacon slicer” rear brake. During 1960 Tony Rudd designed his Mark II version of the car, with a conventional 2 disc rear brake layout, simple rear wishbone suspension and a much lower profile. This resulted in a much better handling car, and for the 1961 Formula One season BRM based their chassis designs on the Mark II. For 1960, BRM campaigned three P48s for Joakim Bonnier, Graham Hill, and Dan Gurney. The P48 debuted in the second race of the season, the Monaco Grand Prix. To the surprise of everyone, including the team, all three cars finished. Bonnier scored points for fifth. However, this proved to be a false hope, as each driver finished only once more. At the Dutch Grand Prix, Hill finished a respectable third behind the Coventry Climax engined Cooper and Lotus of Jack Brabham and Innes Ireland. Sadly, Gurney’s rear brake failed on the entry to Zandvoort’s first hairpin; his BRM rolled into the stands, killing one spectator and injuring several others. After the Zandvoort disaster, BRM scored just once more with Bonnier in the United States Grand Prix. BRM finished the season with a disappointing 8 points.

Bikes have figured prominently in the history of Silverstone, too, and there were plenty of examples of these from the past 74 years here, too.

This sidecar unit dates from 1952 and is a Norton Watsonian.

Among the more recent bikes is this 1972 Suzuki RG500 XR14 with which Barry Sheene won the World Championship.

Comprehensive displays cover just about all the aspects needs to run a motor sport event, show-casing the technology used not just now but through the ages. We learn about the development of the racing car in all its forms, of engines, aerodynamics, suspension, tyres, brakes and fuel and there are video projections of Sir Jackie Stewart talking about safety systems have advanced massively since his days behind the wheel, along with what huge changes in what the drivers wear. There are detailed explanations and exhibits for each of these themes and much more besides. You can see why this is not just something for the casual visitor but also with huge educational value for school children and those in further education.

There are also displays around the logistics of how motor racing can even take place. As well as cars (or bikes) to compete and drivers, you need so much more: race officials, medical staff, safety cars and marshalls, sponsors, a massive logistics operation to have everything in place at the right time, sponsors, advertising and broadcasting and the story associated with each of these elements is also presented.

Although the circuit has a sizeable capacity, which is pretty much filled for big events, such as the Formula 1 Grand Prix, motor sport relies on broadcast coverage to allow a far wider audience to hear and see the action. And for that you need a commentator, or two. Asked to name the most famous voice in motor racing, many would surely nominate the late and very great Murray Walker, who presented not just on the Grand Prix but pretty much everything else that raced on two wheels or four (or more!). There is a lovely tribute that plays showing Murray being interviewed by another great commentator, and ex Formula 1 driver, Martin Brundle. Watching this brought back so much to me, as Murray was “the” voice of motor sport for so much of my life, and we all miss him very much.

There’s one final thing left on the way out. a spectacular theatre experience during which you’re enveloped by a huge video wall that curves away to your sides and up over your head. You sit in a notional racing car and circulate – with appropriate noises – at racing speeds, while great Silverstone moments from all genres of motorsports and across the decades happen all around you. In one helping, this is a huge slice of Silverstone’s august racing history.

This is a fascinating place and there is a lot to see. I asked the museum if their appearance in one of the tasks on “The Apprentice” had resulted in an increased in visitors, and they said it had, though how long this endures before people forget, remains to be seen. Mostly the museum will be visited by those who are interested in motorsport and perhaps those who who are attending an event here – though it should be noted that if there is an event going on, as there was at the time of our visit, you will not get even the slightest of previews of it, such are the layout, screening and access restrictions. I’d certainly recommend it as somewhere interesting to visit. The trick that the museum will need to pull off, though, is how to get people to return time and again, and looking at the displays, I am not sure how easy that will be to achieve, but I am sure they are thinking of it.

More information can be found on the museum’s own website: https://www.silverstonemuseum.co.uk/